Cinematic Melding of Camera and Person Promotes Internal Reflection

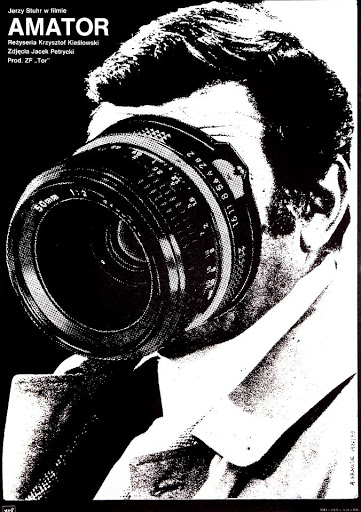

The poster of Krzysztof Kieślowski’s, Camera Buff, depicts a parasitic lens feeding off of the protagonist. (Credit: PolishPoster)

December 3, 2020

In the vast — but short — history of cinema, there has always existed a hypnotic fascination with the relationship between people and cinema’s greatest tool: the camera.

Soviet director Dziga Vertov was the first to make this comparison. Enthralled by the endless possibilities of documentary film, Vertov compared the lens of a motion picture camera to that of an infinitely knowledgeable eye, and crafted a cinematic technique known as Kino-Eye.

Simply put, Vertov’s theory of Kino-Eye would allow the camera lens to capture images that Vertov believed were “inaccessible to the human eye”. According to Vertov, when a director shot untouched life through a lens, the filmic image would produce an inherently different meaning.

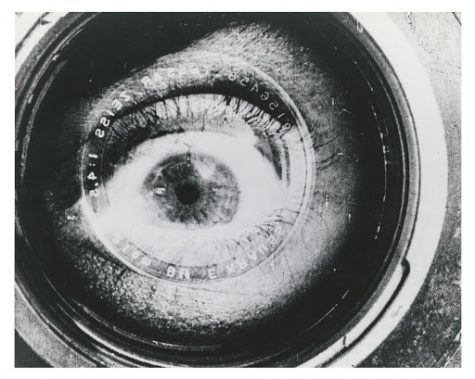

Vertov explores this concept in his revolutionary documentary, Man With A Movie Camera (available on Kanopy and Amazon Prime), which follows an unnamed cameraman as he traverses a Soviet city and captures urban life as it naturally occurs. In the film, there are three levels of image: (1) images of urban life, (2) images of the protagonist capturing urban life, and (3) images of the camera capturing the protagonist capturing urban life. This deluge of image blurs the line between what our protagonist sees and what the camera sees. In a single striking image of an unblinking eye at the end of a camera lens, Vertov summarizes this lack of clarity. And thus, the melding of camera and person began.

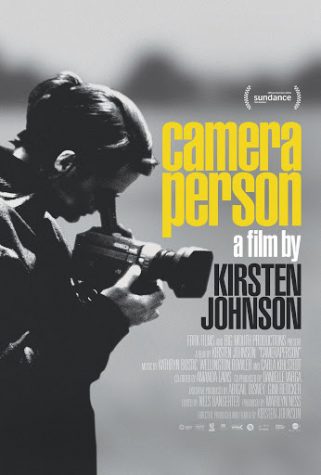

Students of Vertov’s distinct documentary style have come forth in the Twenty-first Century. Documentary-cinematographer Kirsten Johnson explores Vertov’s intrigue into the relationship between camera and person in her aptly titled visual memoir, Cameraperson (available on YouTube and Amazon Prime). The film’s opening is formulaic: a shot of a stormy sky and an expansive country highway just below; a white Honda creeps by; the clouds move, but not by much; and text gives credit to producers and studio executives.

Then, the credits stop. The camera holds on dark clouds. A flare of lightning burns the sky; behind the camera a woman gasps, then chuckles. Credits resume until the camera shakes after the same woman sneezes twice and shakes the camera. A title appears etched into the sky: Cameraperson. Johnson’s self-proclaimed memoir gives an autobiographical account of her life through the discarded footage of her 25 year-long career. It is a film about memories and what it means to stand behind a camera.

Cameraperson is told non-sequentially, like a circle slowly being bent out of shape. The audience meets many people — all of whom have been or are oppressed in some fashion: a rape victim from Bosnia, a boxer from Brooklyn, a taxi driver from Yemen, a prosecutor from Texas, a blind boy from Afghanistan, and a midwife from Nigeria. Through Cameraperson, Johnson shares with the audience short fragments of these people’s lives — stories that, as Johnson explains at the opening of the film, “have marked me and leave me wondering still”. Throughout these various vignettes, Johnson punctuates the catharsis with footage of her own life: her father, her twins Viva and Felix, and her mother, who is three years into the haze of her Alzheimer’s diagnosis.

Until the very end of Cameraperson, the audience never actually sees Johnson; her shadow may be reflected on a Bosnian sidewalk, but her physical being remains a mystery. This visual withholding device limits the amount of time in which the protagonist can be seen, and the audience conditions itself to assign human roles to inanimate objects. The omnipresent “voice behind the camera” is inferred to be Johnson’s mouth, the lens to be her eyes, the edit her blink and the intertitles her thoughts.

Film critic David Fear of Rolling Stone magazine perfectly encapsulates Cameraperson, as “an extraordinary self-portrait and an existential statement: I shoot, therefore I am”. In modifying French philosopher Rene Descartes beautifully simple phrase, “I think, therefore I am” (which he used as a means of expressing reality and human existence), Fear argues that filmmakers such as Johnson pick up a camera merely to maintain their vital organs and preserve contact with reality. In other words, directors have become so anchored in their craft that their existence depends on it, and as a result, they cannot possibly produce a bad film. As famed director Quentin Tarantino put it, “You don’t have to know how to make a movie. If you truly love cinema, with all your heart and with enough passion, you can’t help but make a good movie.”

37 years before the release of Johnson’s Cameraperson, up-and-coming Polish director Krzysztof Kieślowski crafted a film in a similar vein as Vertov before him and Johnson after him. This film, entitled Camera Buff (available on YouTube and The Criterion Channel), follows Filip, a lowly Polish factory worker who, with his beloved eight and a half months pregnant wife, invests in an 8mm motion picture camera to film the birth of his child. Since Filip owns the only camera in his small town, he is immediately named official filmmaker, and films, as he puts it, “anything that moves”. As his films enter regional film festivals and his interest in motion picture grows, Filip becomes engulfed in his newfound hobby and deserts his formerly contented life for the all-powerful camera. Filip’s character arc is similar to that of Michael Corleone in Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather; as the days progress, Filip becomes more and more entrenched in the world of film — so much so, that the film’s poster depicts Filip’s face morphed into a camera lens, as if the device itself were a parasite receiving nutrients from his bloodstream.

What seems to attract Filip to this 8mm mechanical beast is the power he gains from holding it. As mentioned in the film, Soviet Premier Vladimir Lenin once said, “Film for us is the most important of the arts”. Similarly, Adolf Hitler and his Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels capitalized on the power of propagandist cinema to build an ever-expanding Reich. On the other hand, film can convey wholly-virtuous ideas and emotions like no other art. In one memorable moment from Camera Buff, Filip gives his friend, whose mother has just passed away, a roll of film on which he had shot his friend’s mother a few months earlier. As he holds the roll of film, the friend exclaims, “What you do is beautiful… A person may be dead but she is still here”. These are two sides of the same coin. While some argue that film is innately perverse, others say it serves a greater good. No matter where one lands on this spectrum, the simple truth is that cinema is power.

As both Cameraperson and Camera Buff unfold, Kirsten and Filip meld into the almighty camera each wields. Then, something striking happens. Both films — though they are 37 years apart and take place on separate continents — execute the same cathartic ending: the filmmakers turn the camera on themselves. For years, these two individuals have pointed their lens on others. They have delved deep into the psyche of their subjects and have explored powerful and diverse themes. Now, the filmmakers must have their own lens and their own eyes. They must stare themselves down and reveal to themselves whatever it is that they have been so carefully hiding. For Filip, it is too late. For Kirsten, it is not. And so, at the end of it all, ask yourself this: when I turn the camera around, will I like what I see?