The Cinematic Surreality of The Subconscious

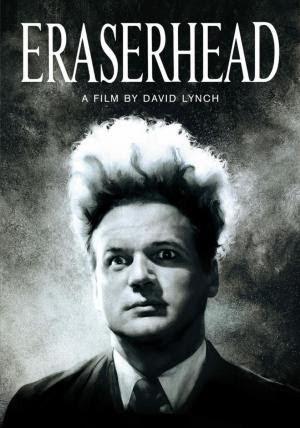

David Lynch’s Eraserhead crafts an immersive atmosphere of post-industrial gloom that leads one to feel their own subconscious repressions slowly begin to emerge above the surface.

December 14, 2020

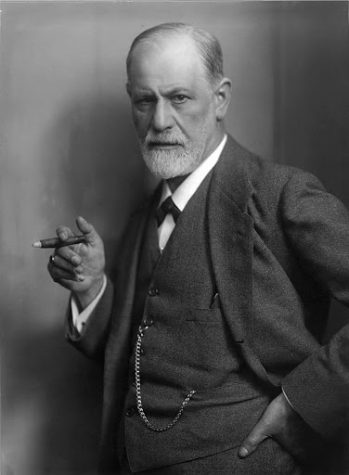

There exists a well-known certainty that human consciousness and all its facets operate on vastly different planes. Austrian psychologist Sigmund Freud first proposed this concept; Freud, intrigued by the curious impulses of his surrounding world, devised a groundbreaking schism in which the human mind could be split. He then labeled the resulting two factions as the “conscious” and the “unconscious”.

Mathematics helps make sense of these two planes (the conscious and the unconscious). On an XYZ plane, there exists a three-dimensional space reminiscent of traditional Freudian perception. The X and Y axes, forever travelling left and right and up and downy, display two-dimensional conscious thought, which is logical, ordered, and noiseless. One acts on their conscious state as society deems it sensible and appropriate. The Z-axis — which establishes the three-dimensionality of the space — however, carves an infinite path forwards and backwards and represents the elusive unconscious, a reservoir of repressed thoughts and memories existing outside of any human awareness. This XYZ plane of human consciousness aids in delineating a direct relationship between the two. Only through access to the unconscious, however deep may go, can one begin to shape and understand the waking conscious. What better lens to study this than through the veneer of the artist and their art?

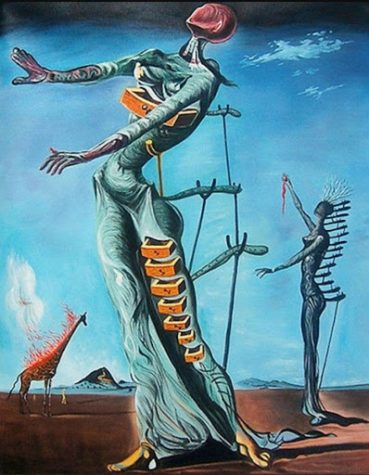

Arguably the greatest twentieth-century artistic iconoclast of his time, Spanish surrealist Salvador Dalí had an obsessive compulsion towards three Freudian themes: eroticism, death, and decay. These themes are present in virtually all Dalinian works, even in those by later artists clumsily attempting to replicate his precise style. Dali captured his dreams and nightmares in a bedside journal, believing, as Freud theorized, they were a direct roadway to the subconscious. Dalí’s 1937 painting, The Burning Giraffe, is a purely chaotic torrent of Dalinian subconscious imagery. The work, which sticks closely to the orbit of Freud’s three central themes, depicts a faceless woman who supports herself with wooden crutches (which happen to be a common motif in Dalí’s work). Open drawers extend from the woman’s legs and torso, and a giraffe burns calmly in the background. Upon inspection, one understandably fumbles toward confusion.

Unbeknownst to many, Dalí was also a successful filmmaker. He and his creative partner, Spanish director Luis Buñuel, inadvertently created the most famous short film of all time: Un Chien Andalou (or The Andalusian Dog, though the title has precisely nothing to do with the surrealist contents of the film). The short (available for free on YouTube) is a masterclass in the exploration and exploitation of Dalí’s eroticism, death, and decay. Buñuel and Dalí wrote the film collaboratively by recalling their past dreams and putting them on celluloid. While brainstorming at a Parisian café, Buñuel told Dalí that he had dreamt of a cloud slicing the moon “like a razor blade slicing through an eye”. Dali responded that he had dreamt of a hand crawling with ants. These two images would eventually become the crux of the film.

The film progresses in a similar manner as that of Freud’s theory of free association; one image may lead to another without rational explanation. The film’s plot, if one ostensibly exists, centers on an unnamed man and woman as they argue and observe peculiar things from their bedroom window. It is through this barren structure that Buñuel and Dalí could access the unconscious, whether it be that of their protagonists, or their own.

Throughout the film, surrealist imagery includes the infamous aforementioned slicing of an eye and insect-infested hands, a grand piano stuffed with the bleeding corpse of a donkey, a Death’s-Head Moth, an impromptu gun duel, transposition of armpit hair, and an amputated hand strewn on a sidewalk. Upon the film’s release in 1929 — the height of the golden age of conventional, formulaic Hollywood cinema — studio executives did not believe audiences had the will-power to interpret such mind-boggling nonsense. While there had been other European attempts to introduce Freudian ideology to cinematography, none were successful. Un Chien Andalou changed this. Dali summarized, “In one evening, this film [Un Chien Andalou] had destroyed a decade of pseudo-intellectual postwar avant-gardism”. Buñuel and Dalí had successfully introduced the Freudian image to the world because they had used the psychologist’s own methods.

In 1971, Dalí appeared on the popular late-night talk show, The Dick Cavett Show, where his practically incomprehensible Catalonian accent and outrageous musings baffled the audience and Cavett. Towards the end of the interview, Cavett asked Dalí, “Mr. Dali… have you, from the beginning of your work — your great craftsmanship in painting — a message to give the people, that we, perhaps, don’t understand?” After an emphatic Dali replied, “No message!”, the audience roared, and the next line of questioning promptly began.

A fervent disciple of Freud and Dalí, director David Lynch is an iconic staple of American cinema. Lynch, who famed film critic Pauline Kael characterized as “the first popular Surrealist”, began his career at the American Film Institute. There, he would write, direct, produce, edit, and compose his first feature, Eraserhead (available on Prime Video and YouTube). The film follows the cowardly and timid Henry Spencer as he learns of and attempts to father an inhuman, hideous, and deformed infantile creature which his girlfriend has birthed and subsequently abandoned. The infant cries incessantly and refuses all food. Sleep-deprived and paranoid, Henry experiences visions revolving around the three Dalinian themes. In these visions, Henry sees himself in a sexual encounter with a neighbor, his child’s head replacing his own, a chicken dinner writhing and bleeding on the plate, his decapitated head stolen to manufacture erasers for pencils, and a lady who torments him from his radiator. Henry’s subconscious drags him ever closer to his greatest repressions, just as Freud theorized.

While this disturbing imagery may be somewhat effective in creating an atmosphere of the subconscious, it would merely turn into a collage of grotesque and unconvincing photographs without the film’s intoxicating sound design. Peter Bradshaw of The Guardian describes the film’s sound design as “industrial groaning, as if filmed inside some collapsing factory or gigantic dying organism”. Still heralded to this day for their work, David Lynch and sound designer Alan Splet dedicated “nine hours a day, for 63 days” to sound mixing and editing to achieve the film’s nightmarish quality. Indeed, Eraserhead‘s ability to craft such an immersive atmosphere of post-industrial gloom leads one to feel their own subconscious repressions slowly begin to emerge above the surface.

Audiences and critics alike have attempted to thematically decode Lynch’s Eraserhead since it’s 1977 release. The most widely-accepted rationalization is that of a fear of fatherhood. Through symbolic horror, Lynch may have captured the universal fear of newfound parental responsibility. This is plausible, given that Lynch himself fathered a deformed infant; his daughter Jennifer Lynch was born with severely clubbed feet. Another theory comments on society’s fascination and fear with sexuality. Film theorist David J. Skal writes in his book, The Monster Show: A Cultural History of Horror, that Eraserhead depicts “human reproduction as a desolate freak show, an occupation fit only for the damned”. Others say that Henry’s vision of the Lady In The Radiator embodies the seduction of death. Lynch would argue that each of these interpretations is correct; the filmmaker’s perspective is irrelevant because the film was not made for him or her. One must bring their own preconceived notions to the viewing experience and discover the film’s meaning themselves. As Russian director Andrei Tarkovsky once said, “A book read by a thousand different people is a thousand different books”.

Life is filled with abstractions. The purpose of art is not to explain these, but to present them in such a way that intrigues the audience to ponder them. Lynch himself has referred to Eraserhead as his “most spiritual film” — not in a religious sense, but instead in a sense of the human spirit. As opposed to all physical surroundings, the human spirit regards the feelings and beliefs of one’s own unconscious nature. And while good artists explore the human spirit, great artists challenge it. Therefore when Lynch is asked why his work doesn’t make sense, he responds with this: “I don’t know why people expect art to make sense. They accept the fact that life doesn’t make sense.”