Beanpole: Cinematic Antiquity in a Modern Age

Through use of revelatory acting and cinematography, “Beanpole”, once and for all, proves the ago-old aphorism: war is hell.

February 1, 2021

Russian director Kantemir Balagov’s most recent film, Beanpole, winces and winds its way through war-torn Russia in the same way that a loose trolley would fly through the streets of New York City: unrelentingly, dangerously, and insatiably. Yet one cannot look away. Through use of revelatory acting and cinematography, Beanpole, once and for all, proves true the age-old aphorism, “War is hell”.

The film begins in Leningrad at the conclusion of World War II. Russia has withered, and it’s people are faring far worse. Their knuckles are worn, and their noses are chapped. In the beginning, Balagov’s camera sees all. He perfects an aching portrait of Russia before slowly closing his aperture on the film’s two main characters: Masha (Vasilisa Perelygina), a hopeful, ambivalent young soldier, and Iya (Viktoria Miroshnichenko), a sagging, sluggish, and PTSD-stricken nurse. Their relationship may be one of the most confounding and intimate in all of cinema.

Iya, in every frame she inhabits, appears sickly and towering — like a beanpole. She is the tallest character in the film, but she is also the quietest. Iya was a soldier on the front lines before her discharge because of post-concussive syndrome that causes her to experience fits of abnormal “freezing”. Iya, now a nurse for injured veterans, is surrounded by the sorrow she seemingly detests.

It is unlikely that Iya would be different were she to have not lived through the war. Iya is the type of person whose soul burned long before she felt fire. This characterization emphasizes the power of Viktoria Miroshnichenko’s marvelous acting. Her ability to create nuance — a story in the smallest wrinkles of her skin — is perhaps best akin to Gena Rowlands’ performance in John Cassavetes’ A Woman Under The Influence. Miroshnichenko’s wilting shoulders weigh as heavily upon the audience as they do upon her.

Masha, on the other hand, is more sanguine and warm-blooded. By default, her performance lacks considerable weight — though it doesn’t cause the film to drag; rather, it gives the film wings. Contrasting Iya’s harrowing solemnity, Masha breathes new life into the picture — though she is not without her own demons. All Masha wants is a child; she once had one — little Pashka — but he is killed early in the film under the care of Iya, a flagrant warning to all unsuspecting audience members that ‘it doesn’t get more fun from here!’ Through guilt and blackmail, Masha convinces reluctant Iya to bear her child. Masha’s rosy cheeks and youthful anything-can-happen attitude plays off of Iya’s hollowness so beautifully that one questions how the two tolerate each other at all — in fact, at most points, they don’t.

While the dynamic kinship between Iya and Masha enters many stages of assault, the two feel obligated to stay together in order to save their own sanity. They often devolve into fist fights and brawls, only to recover through intimacy. A tinge of homoeroticism runs throughout the whole picture in the most brilliant way, and its subtlety leaves the audience reaching for more.

There is, perhaps, only one moment of levity present in the film. After receiving a vivid green dress from a dressmaker next door, Masha asks her neighbor, “Can I twirl?” with a childlike sense of apprehension not yet seen from her. Masha proceeds to spin violently as the camera focuses on the twirling folds of green cotton. She soon becomes dizzy and hits the walls of Iya’s tiny Russian flat, weeping and wailing as she rips the dress off of her body. When Iya runs to embrace her, Masha fights back. After she relents, the two share their only moment of intimacy. This scene serves as a microcosm of the film, as nothing is pure in this world — not even a lowly green garment. The immensity of both performances tap into a rawness of humanity most tenth-rate actresses leave wholly on the sidelines.

The two young heroines — Vasilisa Perelygina and Viktoria Miroshnichenko — give the picture depth as great as a bottomless reservoir. They complement one another in every way, even when hurling insults at each other. Despite their age, it appears that the two actresses thoroughly studied the classics. Danish director Carl Theodor Dreyer and Swedish filmmaker Ingmar Bergman both believed that motion pictures revolved around the content of the human face, with Bergman famously saying, “For me, the human face is the most important subject of the cinema”. No film — with the exception of those by Dreyer and Bergman — has implemented this concept as strongly as Beanpole does. The weathered, crusty faces of Marsha and Iya tell us more than any line of dialogue ever could. Masha looks as modern as anything, while Iya wears a face of yore. They are worlds apart, together.

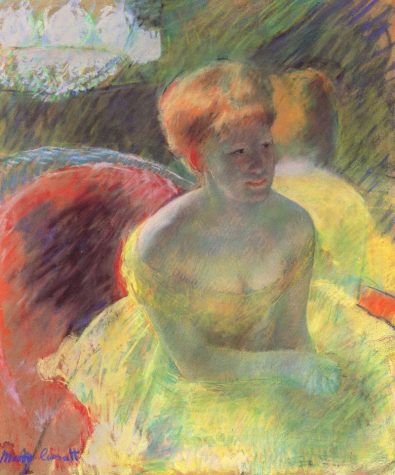

Cinematographer Ksenia Sereda’s unique cinematic style is best described as a quasi-conglomerate of the lyrical brushwork of Monet and the religious iconography of the Byzantine Empire. Sereda colors the film’s palette with an astute vibrancy only seen in nineteenth-century impressionism. Artistic impressionism began as a way to render light — particularly it’s fleeting qualities — as realism stepped aside for heightened emotionality. Idiosyncratic angles became the norm, and an expansive and wide-ranging color palette was introduced. Though Beanpole is set in what may be one of the dreariest moments in human history, its cinematography is ripe with color and shadow, as Sereda uses her camera to paint the silver screen in precisely the same way that Monet and Renoir did a century earlier.

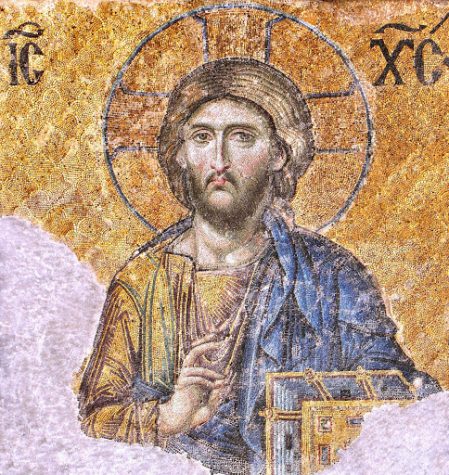

Sereda frames her shots like iconographic Byzantine paintings, which portray a stoic figure shrouded in dense light as a halo, or nimbus, gathers around his or her head. The artwork is consistently two-dimensional, and the figures are fundamentally inert. This style is the greatest visual representation of Iya: she is inherently unwavering; Iya is static, and flat, in the greatest possible manner. One can only assume Sereda derived her framing and compositions, at least subconsciously, from this magnificent artwork.

If one thing stands out above all others — if there is one truth that can be derived from Balagov’s sobering picture — it is this: Beanpole is a film of young people. Despite the film’s meditative dejection, something innately fresh runs through the its every fiber. This can be attributed to the the film’s production. Beanpole was only Balagov’s second feature; the director wrapped the project at a staggering twenty-eight years old. The film’s primary billing — actresses Vasilisa Perelygina and Viktoria Miroshnichenko, aged twenty-four and twenty-six respectively — were complete newcomers to the motion picture industry. Beanpole was their first major production. Although the film’s cinematography is at a level of mastery most take years to reach, Ksenia Sereda was only twenty-four years old when she shot the film. When fresh blood directs an actor, sheds a tear, or composes a shot, the final cut will — by definition — acquire that same vibrancy, regardless of the content. It is no coincidence that director Robert Zemeckis made the awe-inspiring Back To The Future at thirty-three, and the life-less, mind-numbing Welcome To Marwen at sixty-six.

Beanpole first premiered at the 2019 Cannes Film Festival, where it took home the award for Best Director and the FIPRESCI (The International Federation of Film Critics) Prize for Best Film in its category. The film was also selected as Russia’s entry for Best International Feature Film at the 92nd Academy Awards.

Knowing this, one asks, “How does something this unconventional and unfamiliar receive an audience in such a modern, fast-paced world?” The film certainly doesn’t adhere to convention. If one were to place a label on the film, Beanpole would find company in a select sleeve of motion pictures entitled ‘slow cinema’. ‘Slow cinema’ is a genre of art filmmaking characterized through the use of long takes and minimalism, and a focus on the contemplative nature of humanity rather than the narrative. This, whittled down to its lowest common denominator, perfectly describes Beanpole in every possible way. ‘Slow cinema’, once referred to as art-house cinema (though the two have subtle differences), first gained popularity in 1950’s Europe with directors such as Ingmar Bergman, Federico Fellini, and Robert Bresson. Kantemir Balagov — who has demonstrated a unique, introspective vision so inviting one can only throw praise at him — can now be added to that list.

To most, Beanpole will come across as self-aggrandizing, high-brow, and pretentious melancholia. But this interpretation misses the point. For those few who stick it out — for those few who see the film through its every whim and submit to its every intrigue — Beanpole hits the chest where it hurts the most, then promptly cleans up the blood and sutures the wound. Every moment of the film enraptures the audience in a place where one does not want to be, but a place from which one will not, can not, and dare not leave.

“Beanpole” is available to stream on Kanopy.