John Oliver: A Modern Muckraker

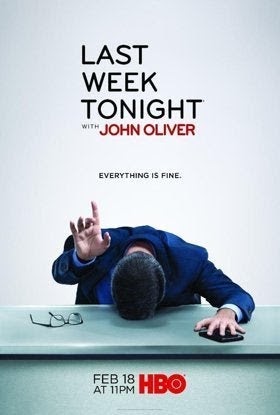

John Oliver’s Last Week Tonight is Last Week Tonight is licensed under HBO, which allows for a full-fledged screaming match speckled with profanities.

March 24, 2021

Every epoch has its issues. The Cretaceous Period wiped out dinosaurs, the Middle Ages plagued an entire continent, the Age of Discovery forced Natives from their homeland, and the Gilded Age coated a system of political and industrial abuse in shiny, glimmering gold. And as all ages have their messes, all messes — including ours today — have their muckrakers.

The term “muckraker”, as it exists today, came about in the early twentieth century; it was used to describe those who pushed the mire off contemporary issues, exposing them as they truly were to the public. These journalists typically ‘raked’ with their pen (though the advent of photography encouraged some to capture images, which dragged an unwashed public even further into the muck). It is at this conjunction where the unique pillars of Oliver’s journalistic techniques — his unique mix of drunken humor, public appeal, and Progressive Era muckraking — unfold.

Created in 2014, John Oliver’s Last Week Tonight is now a staple of American comedic-journalism alongside Trevor Noah’s The Daily Show and Stephen Colbert’s The Late Show. Oliver compensates in every way possible for what the latter two programs lack. Public broadcasting censors restrict Noah and Colbert from finding the proper vigor to drive the point home. Last Week Tonight, however, is licensed under HBO — a private enterprise — which allows for a full-fledged screaming match speckled with profanities. Oliver wisely uses this feature to his advantage.

It is for this reason that Oliver can rightfully be crowned a modern muckraker, while Colbert and Noah cannot: muckrakers of both the Progressive and Contemporary Eras are not restricted in their journalism by the censors of a parent company or personal censors of modesty. Oliver is not a modest man — though neither was Upton Sinclair.

Another litmus test of muckraking is the journalists’ call to public appeal. To make an audience truly care — not just laugh or cry or cringe — one must present the piece in such a way as to solicit a response or action, not merely a reaction. In its depiction of the horrors of the early twentieth century meatpacking industry, Sinclair’s The Jungle (1905) led to the passage of the Meat Inspection Act of 1906. Indeed, public action was fierce; Sinclair said of his novel, “I aimed at the public’s heart, and by accident I hit in the stomach.”

Oliver follows Sinclair’s realization and aims only at the stomach. The modern muckraker broadcasts from his gut, and hopes to hit his audience in precisely the same way. Rarely — if ever — does Oliver go for the teary-eyed approach as so many others do. Rather, Oliver knows that a gut feeling is far more potent than an intellectual — or even emotional — attachment.

Drunken humor — the third pillar of Oliver’s muckraking — is often overlooked. Nearly everyone agrees that his show is somewhat humorous, even if the sacrilegious nature of the humor offends some. While muckrakers of yore did not attempt to persuade the collective public stomach by being funny (their intention was exactly the opposite), Oliver understands that the current world is quite different from that of the 1920’s and that desperation no longer sells. Oliver’s self-deprecating blindness and his persistent and shameless use of four-letter-words break down an audience’s inhibitions and allow them to sit comfortably in their chairs — at least until the other two pillars come along.

Each of Last Week Tonight’s greatest hits — including those on Televangelism, Net Neutrality, the Miss America Pageant, the Coal Industry — have distinctively contributed to what has become known as the “John Oliver Effect.” This phenomenon lauds the journalistic talents of Oliver and his staff, and represents just how much influence the man has over American culture and legislation. Oliver’s raking the grime off industry and politics is reminiscent of a particular era in American life. John Oliver leads the modern era in which journalists write the laws, sign the bills, and rule the day.