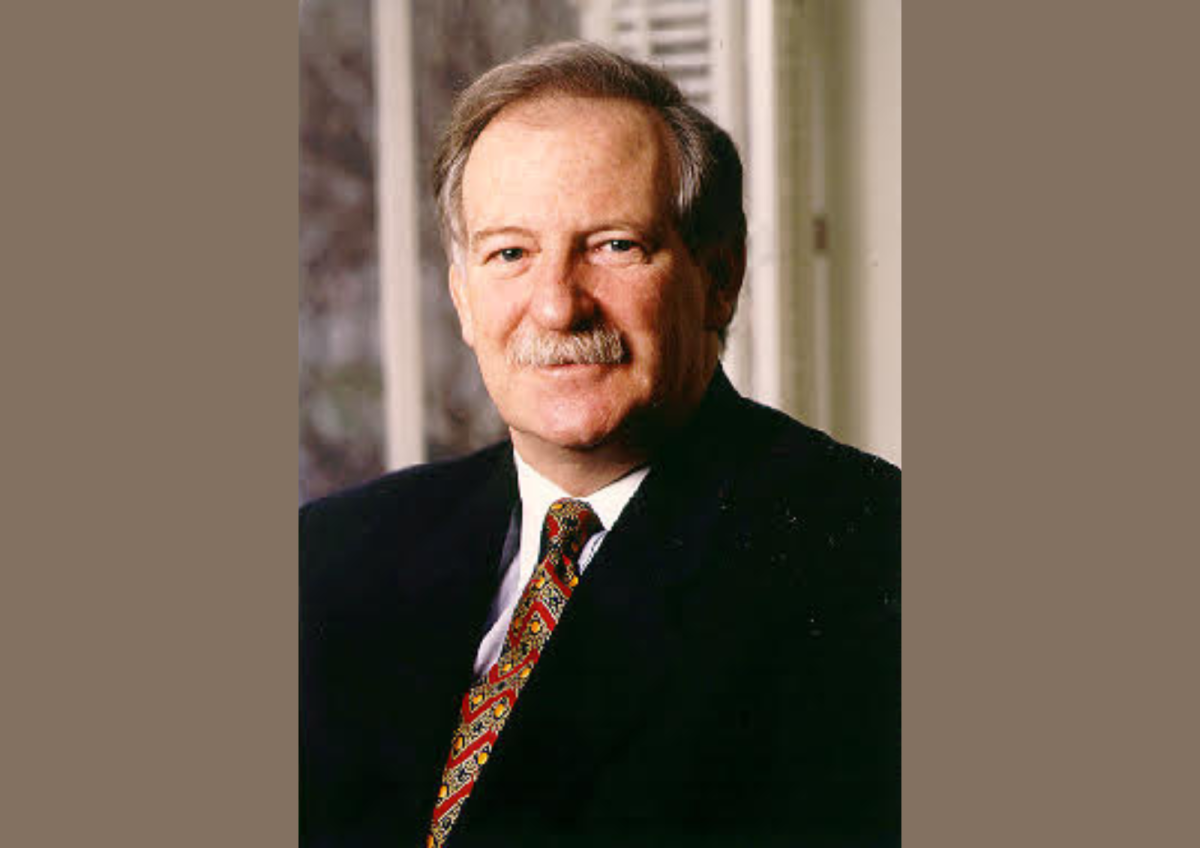

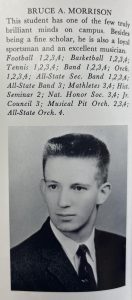

Northport High School alumnus Bruce Morrison is an attorney, politician, and activist. He served as a member of the United States House of Representatives from Connecticut’s 3rd congressional district from 1983 to 1991. Mr. Morrison is known for his work on human rights issues, specifically within immigration, throughout his time in office. After leaving Congress, Mr. Morrison has continued to be an important voice in immigration advocacy and the peace process in Ireland. We had the privilege of sitting down with Mr. Morrison to talk about his time in high school, his journey since then, and his advice for students today.

If you were teleported back to Northport High School, what’s the first place you would go and why?

If I were teleported back to Northport High School, I would probably go to one of two places. I’d either go to the gym and the tennis court to remember my not-so-heroic athletic achievements of the day. Or I would go to the chemistry lab, which is where I started my first career. The other main thing I did when I was high school was I played the french horn in the band and orchestra. So those were the three focal points of my high school life.

Did you have a favorite class or subject in high school?

When I was going to high school in 1957, the Russians launched the first artificial satellite, Sputnik. That took America by surprise. I imagine the spies already knew, but the average person didn’t. That led to a hurried investment in science education and math education. So there was a real push in that direction. If you were a good student, there were more advanced options in the sciences than there were in the humanities or something else. I had a number of good teachers in math and science, and in particular, there was a guy named Gerard Kass, who was a chemistry teacher. And he was, he was a really goodteacher. He loved chemistry and he taught it with passion. It really affected me. I became friendly with him outside of the classroom. Unfortunately, a few years later, he killed himself, so obviously he had things going on in his private life that we didn’t know about at school. But he was a great teacher and he made me like chemistry. I don’t know if I would’ve liked chemistry anyhow, but because he was so passionate about it and such a good teacher, I really got into it.

What about your time in high school stood out to you?

My memory is that it was an easy time. I enjoyed it. My mother was the librarian at Northport Junior High School, and before that at Ocean Avenue. So we were connected to the school system. My father commuted to the city every day so that gave us a connection to Manhattan. But we were living in many ways apart, Northport wasn’t really a suburb. It was more like an exurb at that point. And Long Island had potato fields. Therewas a potato field across from my house. Of course, it’s houses now. So, it was such a different place from what it is now. I remember Northport High School as a fun experience. There was the stress of getting into college and all that, which hasn’t changed. But overall it was a relatively stress free world. We didn’t really worry. I mean, we didn’t worry about nuclear war, I don’t think, although we did these duck and cover drills where we had to duck under our desks to protect ourselves if the Russians launched a nuclear attack. That wouldn’t have done us much good. We did those things, but it wasn’t like we were worried about our future. The world around us was not threatening. It was a very different time.

Do you remember a large Irish American population in Northport?

I do intellectually, but I don’t experientially. I wasn’t raised Irish American. I really got into the Irish issue when I was in Congress, largely because people in my congressional district were very concerned about the issues. And I was working very hard on human rights issues and I considered Northern Ireland to be a challenging place from a human rights perspective. But my father’s family was from Northern Ireland and Protestant, so I wasn’t an Irish Catholic. My mother’s family were German Lutherans. So, if I was raised in any ethnicity, it was more German than Irish. The Irish community would’ve been going to St. Philips and would’ve been more in the Catholic world, which I wasn’t really a part of. That’s not part of my youth. That’s part of my adulthood.

Professionally, what were your goals in high school and how did they change throughout the years?

I remember taking PSATs and they asked what your educational aspiration was. I put down a PhD and my mother was thrilled because she was an educator, and the idea that I would go that far in educational level she made her very proud. She praised me a lot for that ambition. So that was nice. The way I like to tell the story of my mother in all of this is when I told her I was going to get a PhD, she thought that was great. And when I went to MIT and studied chemistry and then went to graduate school, she was completely excited with that. But then when I decided to become a lawyer, she said, nah, not so sure. And then when I said, “I’m gonna run for Congress,” she said, “now I know I failed.” So from her perspective going away from a PhD in chemistry to a law degree, to a political career, that was like climbing down the ladder. I’d say that the household I was raised in was not very political and was not enamored of lawyers and really loved educational things.

If you had a conversation with yourself in high school, do you think you would be surprised by where you are now?

I didn’t see it. I had a guidance counselor, and I don’t know how people feel about guidance counselors these days, but I thought she was a silly old lady. She was, she was older. Maybe she was in her fifties, maybe she was in her sixties. But she looked at my standardized test scores and I had good scores, not only in math and science, but in English and humanities. So she thought I shouldn’t run off to MIT because she thought I would be tracked into the sciences, and that wasn’t necessarily what I would find most fulfilling. And she was very perceptive, but I thought she was just silly. She said, “Oh, why don’t you go to one of these programs where you go three years in a liberal arts school and then you transfer for two years at a technical school.” I think she probably figured I’d never leave the liberal arts school. I didn’t do that. I went to MIT and I graduated from MIT in three years. And then I did exactly what she said I would do, which is, I got very into my science and I was good at it, but as soon as my life came to a point where I had to choose between the grunt work of being a bench scientist going into the lab and doing experiments all day or going to the streets and doing organizing, the streets always won. That took me until my second year at graduate school before I realized that. And that’s partly because I didn’t look left, I didn’t look right,.I just looked straight ahead and worked really hard to get out of MIT in three years. And there really wasn’t much time for doing other things. Although at MIT, I got involved in student politics, and student politics never interested me in high school because I thought it wasn’t very meaningful. But at MIT we ran our dormitory so being the head of the dormitory was actually running something, and it was of interest. I guess that was the beginning of thinking maybe I like something better than I like science.

What would you say to your high school self?

Don’t take yourself so seriously.