Dr. Strangelove: The Predecessor of Saturday Night Live

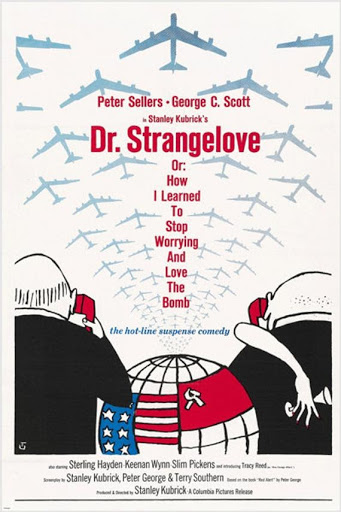

Stanley Kubrick drafts a satirical masterwork of laughs and nuclear annihilation in “Dr. Strangelove Or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb”.

November 11, 2020

Title: Dr. Strangelove Or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb

Director: Stanley Kubrick

Year: 1964

Rating: 5/5

“Gentlemen! You can’t fight in here, this is the War Room.”

As defined by the Oxford English Dictionary, satire refers to the “use of humor, irony, or ridicule to expose and criticize people’s stupidity or vices”. Ever since the Founding Fathers set down the First Amendment to the Constitution — guaranteeing the rights to freedom of speech and freedom of the press — enterprising critics of contemporary politics have stayed out of the shadows. They found, however dire the political and social atmosphere, that the people of the United States deserved an outlet of absurdity and cynicism they didn’t receive in their daily lives. In 1964, as film was becoming an increasingly dominant and all-powerful medium, Stanley Kubrick drafted a satirical masterwork of laughs and nuclear annihilation in Dr. Strangelove Or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb.

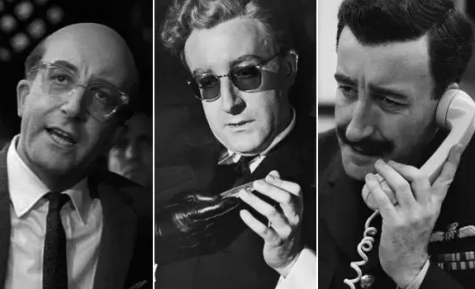

Veteran actor Peter Sellers plays each of the film’s three defining characters: Captain Lionel Mandrake, President Merkin Muffley, and Dr. Strangelove.

Captain Lionel Mandrake, a charismatic yet bumbling British officer, is tasked with retrieving communication codes from General Jack D. Ripper (an obvious homage to the infamous serial killer ‘Jack the Ripper’), a deranged military commander who has ordered a B-52 fighter jet to release an atomic bomb on the U.S.S.R. Remember. At the time of Dr. Strangelove‘s premiere in January 1964, the Cuban Missile Crisis — the closest the world came to nuclear war — was fresh in viewers’ minds. Despite the many tangents along the way, it is this tension that glues the film together.

President Merkin Muffley is a weak and ineffectual leader. Although he and and thirty of his top generals sit in the War Room and debate solutions to the crisis, the President only listens to the ones that will earn him praise in future history textbooks.

The titular Dr. Strangelove is President Muffley’s scientific advisor. His archetypal “mad scientist” behavior contradicts his seat in the War Room and his intimate staffing position with the President himself.

The film, reduced to its simplest terms, reveals a common trait between these powerful characters: they are lustful, vain, caricaturistic, and — sometimes — psychotic. General Buck Turgidson, one the President’s top officials, is first introduced to the audience through his lover — either a prostitute or a woman with whom he has had an extramarital affair. General Jack D. Ripper, leading commander of Burpelson Air Force Base, has gone inexplicably insane, veraciously firing a machine gun at oncoming “Commies” through the window of his office while spouting outrageous conspiracy theories. Kubrick paints each of these men as parodies of themselves so crude that one can’t help but laugh at their foolishness. This is the satirist’s greatest gift. And this technique is certainly not new.

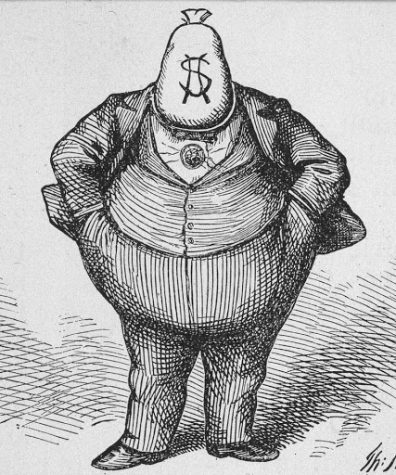

Editorial cartoonist Thomas Nast (1840–1902) may be the most famous American satirist. Nast was a staunch critic of William M. “Boss” Tweed, the leader of the Democratic political organization Tammany Hall from 1858 to 1871. In his cartoons for Harper’s Weekly, Nast characterized Tweed as a corrupt and money-grubbing politician. His most famous cartoon depicts Tweed as a parody of himself; his head has fallen off and has been replaced by a bag of money.

125 years later — 11 years after the release of Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove — television producer Lorne Michaels created the sketch-comedy show Saturday Night Live. Ever since it’s start in 1975 — when it found its foot with Chevy Chase’s impersonation of then-President Gerald Ford — Saturday Night Live has maintained its biting satirical edge. Saturday Night Live has always focused on the contemporary politics of the day, with the most recent impersonations being those of President Donald Trump and his Democratic challenger (and now President-elect) Joe Biden. With everything going on during the 2020 election — increased partisanship, the COVID-19 pandemic, a bleeding economy, and racial unrest — Saturday Night Live is an outlet of absurdity and cynicism that the American people deserve in their daily lives.

As times get tougher, satirists thrive. Thomas Nast saw a corrupt politician and drew him as such. Saturday Night Live saw a struggling democracy and played it for laughs. Stanley Kubrick saw a world on the brink of extinction and made a film of the men who got brought it there. The importance of satire runs through the ages.

Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove Or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb is available on YouTube and Amazon Prime.