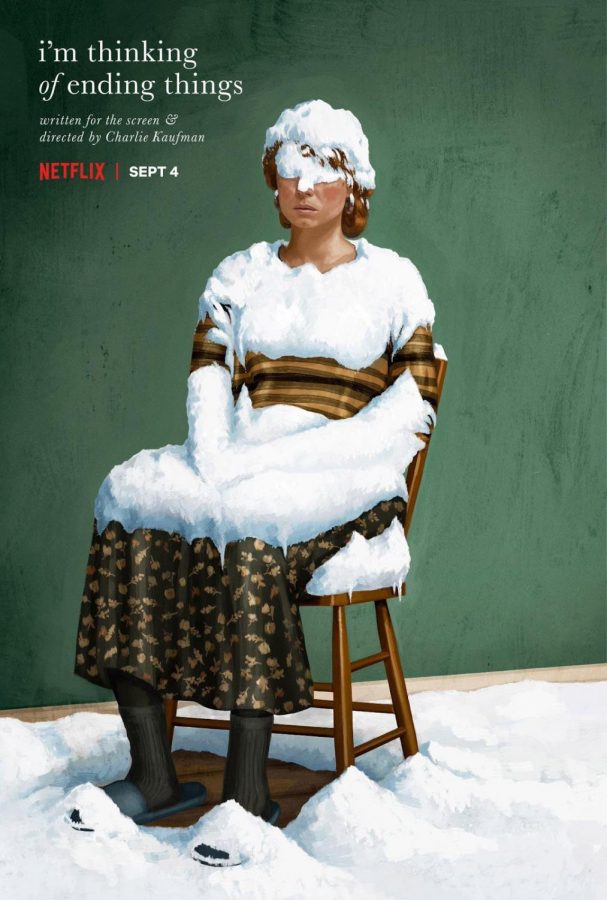

I’m Thinking Of Ending Things: Existentialism Through Absurdity

Charlie Kaufman’s latest film, I’m Thinking Of Ending Things, presents existential philosophies to a modern age through the use of absurdity and surrealism.

January 7, 2021

If philosophers of the cinema exist, writer-director Charlie Kaufman would surely be named among the greatest. His new film, I’m Thinking of Ending Things, based on Iain Reid’s novel of the same name, is an existential cinematic assault so heavy one can practically smell the minds of Camus, Nietzsche, and Sartre working simultaneously to write Kaufman’s brilliant picture.

Though practically untouched in the film industry, the literary concept of “stream of consciousness” — in which a character’s thoughts are presented to an audience as they come and without filtration — is perhaps the best description of Kaufman’s latest movie, and more broadly, his entire filmography. Kaufman presents the free-flowing thoughts of the protagonist — an unnamed woman travelling with her boyfriend, Jake, to his parents’ upstate farmhouse — without judgement. Rather, the woman serves merely as a blank canvas on which to paint different philosophical and intellectual questions nagging at what the film believes to be a modern audience.

As they drive along snowy roadways with scenes lasting upwards of 22 minutes, the protagonist and her boyfriend discuss American academia, from the suicide of essayist David Foster Wallace to an obscure Pauline Kael film review of John Cassevetes’ A Woman Under The Influence. As this discussion occurs, the woman’s thoughts are read aloud à la “stream of consciousness”, giving insight to her thought processes. “I’m thinking of ending things”, she repeats to herself over and over again. There is a certain intellectual dreariness present in Kaufman’s work that leaves a very sour, confusing tablet on the tongues of most viewers. The often marvelously thrilling (and equally unsettling) bits of sugar Kaufman throws at the audience are not enough to neutralize the understandable sourness of his own brand of existentialism.

In one particularly moving sequence, the protagonist, while seated at a pastoral dinner table littered with comfort-food-fixings, is bombarded with questions into her line of work (a characterization of this woman that changes throughout the movie; she begins as a waitress and ends as a molecular physicist). In this particular instance, Kaufman has made the woman a painter. She shows her artwork to Jake’s father, which he attacks with visible confusion. He does not understand how a landscape can feel “melancholy”, as she describes it, without the frown of a face saying so in the foreground. She attempts to explain painterly theories, but he seems unable to grasp them. The woman then responds with perhaps the film’s most telling line: “I try to work with a sense of interiority”. She explains that the painting depicts melancholia because that described her emotional state at the time of the painting’s creation. Since she — and, in turn, Kaufman — lives by an innate sense of interiority, she is capable of higher-level comprehension, while Jake’s father, for example, is not. With this, Kaufman seems to let slip the film’s only legible — though still greatly ambiguous — theme: without an understanding of the inside of one’s head, the outside becomes an unintelligible dystopia.

Released to Netflix on September 4, 2020, as a pandemic roars and uncertainty abounds, I’m Thinking of Ending Things is a timely film with no coherent message, theme, or plot. While its philosophy may seem overbearing, the film does not laugh at those who do not “get it”; it can be argued that Kaufman’s characters themselves don’t quite “get it”. At times when the movie theater may seem a barren and dull place, riddled with viruses and banal superhero flicks, it is precisely this film that should be celebrated as a landmark of cinema in this strange new age.