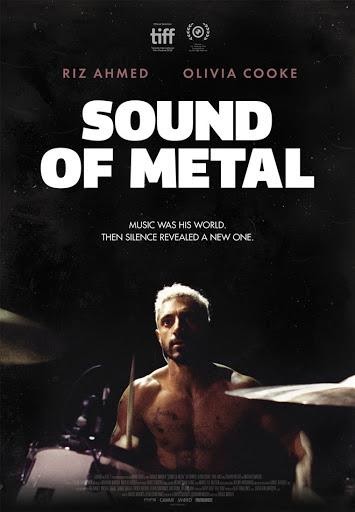

Sound of Metal: Silence in a Noisy World

Darius Marder’s recent film, “Sound Of Metal”, tells the simple story of metal-rocker Ruben Stone as he succumbs to and finally accepts the loss of his hearing.

January 25, 2021

Darius Marder’s first fictional feature, Sound Of Metal, is a simple story told through sound in a world in which none exists. The film follows metal-rocker and former heroin addict Ruben Stone (Riz Ahmed) as his thunderous drumming, coupled with his girlfriend’s high-pitched guitar wails, leave him deaf and without a scrap of hope to be found. Ruben eventually finds some hope in a deaf community, where the crux of the film takes place. That’s it. There exist no subplots, nor unnecessary tangents. In the hands of a lesser director, Ruben would likely be in the loving gaze of a similarly afflicted deaf person; or perhaps he would receive a call informing him that his parents are greatly ill. But Marder knows that there is much drama to be found in simplicity, putting blinders on the sides of his camera in the same way one would a race horse. Marder prefers that the audience revels in the simplicity of the story, allowing the audience to absorb the searing drama like a ShamWow in a bathtub.

The film’s opening is a powerhouse of musical emotionality as viewers enter Ruben’s world through his only passion — music. He is performing a concert for blood-thirsty, shirtless metalheads covered in tattoos as a booming kick drum eats away at his ear canal. He exits the concert venue to a piercing hiss that anyone afflicted with tinnitus has come to know. Thus begins Ruben’s second life.

It is at this point that the film’s inevitable win for Best Sound Mixing becomes apparent. Sound design, unfortunately, has come to be known as the ugly step-child of film production; few know what it is, how it works, or what it can do. The film’s sound, as well as it’s cinematography (shot on glorious 35mm), centers around the conflict between objectivity and subjectivity. Nicolas Becker, the film’s almighty sound designer, straddles a beautiful line between this dichotomy. A close-up of Ruben indicates subjectivity. The audience hears the world as he does — that is to say, not at all. The film often jumps between sound and silence, presenting both sides of life in the way that a good novel or an above-average college thesis does. It is a challenging feat that cuts between two perspectives with such clarity and emotional poignancy — but somehow, Marder pulls it off.

The film continues as the camera documents Ruben’s life in a deaf community. Although Ruben states earlier in the film that he does not consider himself a religious man, one with any sense of Christian theology can interpret this community as Ruben’s own Purgatory. Ruben wants hearing aid implants, but they cost too much. He wants his girlfriend by his side; however, he can’t hear her one bit. Ruben is stuck in limbo, absent from both the world and deaf community at large. In one particularly moving sequence, Ruben eats at the communal dinner table as sign language flies from chair to chair. Since he cannot read sign language, he is further alienated from his environment.

Ruben’s first assignment from Joe — the leader of the community and a self-described troubled soul — to “learn how to be deaf” is the perfect remedy of humor the film desperately needed. By the end of his tenure at the community, Ruben achieves this goal. And while he has become fluent in ASL, one can still sense Ruben’s unhappiness: he has not left Purgatory — rather, he has only learned to adapt to it.

The film’s indirect theology carries significant weight. Throughout the film, Ruben exists in all three states. He floats through Heaven and Hell passively, with his newfound deafness serving as the Purgatory he can’t seem to escape. Community leader Joe stresses the sacred “stillness” of all things — the purity of silence. As he puts it, “deafness doesn’t have to be a handicap”. A vagrant mind is life’s own worst Purgatory. One chooses, everyday, whether it will be hellish or heavenly. It is what one makes of it.

As a total package, Sound Of Metal is rather quiet in its mannerisms. Marder’s direction is focused, and his message transparent and consumable. That is, until Ahmed’s raging performance or Becker’s dynamic sound design turns the tempo up to 11. Both of these worlds — the quiet and the fierce — are to be equally relished. Sound Of Metal sits just as hard as it sprints.

“Sound Of Metal” is available to stream on Amazon Prime Video.