Introvert or Extrovert? Breaking Down This Social Tendency

The population of the United States, along with that of the rest of the world, is split fairly evenly amongst introverts and extroverts.

January 26, 2021

The population of the United States, along with that of the rest of the world, is split fairly evenly amongst introverts and extroverts. How much do we really know about the introvert-extrovert scale? It depends on whom is asked. Some will claim we know plenty about the scale commonly used to categorize social behavior, while others will say we know little.

A common misconception focuses on the extremities: a person is either a bubbly extrovert, or they are an anti-social and stay-at-home loner. Psychologists, however, argue that there is a middle ground made up of ambiverts. In fact, psychologists believe that everyone is an ambivert with a leaning toward one side of the scale. In other words, no one is entirely introverted or extroverted.

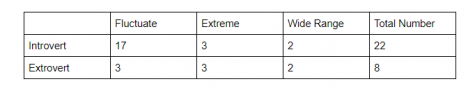

In a survey designed by Port Press freelancer Jules Nguyen, a whopping 22 of the 30 respondents (73.3 percent) described themselves as more introverted than extroverted. Out of those 22, 17 indicated that they “fluctuated” within the introvert side of the scale. Only three of the self-claimed introverts said they were “extreme” introverts, and only two said their personalities varied greatly across the scale. This data reveals that the majority of “introverts” are introverted to varying degrees, and that there are only a few who consider their personalities to significantly vary or be extremely introverted.

Interestingly, the data collected from the eight respondents (26.6 percent) that claimed they are extroverted followed a slightly different pattern than that of their counterparts. Only three of the eight stated that they “fluctuate” within extroversion. While two extroverts said that their personalities covered a wide range on the scale, three considered themselves to be “extreme” extroverts.

So, why do some people fluctuate within their ends of the scale while others hover at the extreme end? And why were the overwhelming majority of survey respondents introverts?

A theory referred to as homophily offers an explanation. The theory states that people of similar levels of introversion or extroversion tend to befriend each other. The survey’s creator, Jules Nguyen — an introvert — had asked her friends to take the survey. According to the theory of homophily, Nguyen naturally distributed the survey to more introverts. Homophily also explains why many extrovert respondents indicated on the survey that they would likely become good friends with another extroverted person.

So, what is the difference between extroverts and introverts?

In short, social interaction outside the main circle drains introverts, who tend to ‘recharge’ themselves through time spent alone or with close friends. The opposite tendencies apply to extroverts. Isolation is tiring for extroverts, who fill their social battery by being with more people.

Scientifically speaking, one’s place on the introvert-extrovert scale isn’t solely a product of genes and upbringing — though the two are significant factors. Personality comes down to brain wiring. Brain scans have shown that introverts have thicker prefrontal cortices — the part of the brain that controls the thinking process — than extroverts. Although this neurological difference translates to less impulsivity for introverts, it brings the downside of upturned risk of anxiety and depression. Brain scans of extroverts reveal that dopamine, a hormone that evokes happiness, is activated more strongly in winning scenarios and in situations involving human connection. This phenomenon is directly linked to extroverts’ love of human connection. While the brains of introverts still produce dopamine in social scenarios, extroverts produce much more; as a result, social experiences provide a greater benefit for extroverts than they do for introverts.

These social tendencies are not concrete; research shows that people reach peak extroversion as young adults and gradually become more introverted as they age. The responses to the Port Press survey reflect this trend. Many of the introverted respondents said that they have “come out of their shell” more since childhood. This transition is due to evolution. The quality of being extroverted corresponds to a better ability and a greater willingness to make friends — a critical skill for finding a future partner. As a person and his or her lifelong friends age and start families, the need for new friends and partners dissipates, leading to introversion.

Overall, there is a lot more to characterizing introverts and extroverts than initially meets the eye. Whether its homophily, neurological differences, or evolutionary transitions between personalities, there is much to learn about the seemingly-simple personality scale.